by Pascal Jacob

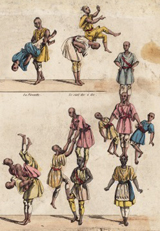

Etymologically, an acrobat is someone who moves around on their extremities. It is a way of playing with the body, of having fun with the constraints of gravity, of producing an effect of surprise and evoking admiration. Success in acrobatic movements comes through regular training and physical development on the part of the artist. Acrobatics has this in common with gymnastics, or gumnòs in Greek, which means nudity. The gymnasium was a place where one practiced naked in preparation for athleticism, an ambiguous term for fight and combat. These roots predispose the acrobat, traditionally represented naked on frescos and Greek urns, to claim value for these physical skills, but also to take inspiration from energy and confrontation to characterise certain feats.

From Babylon to Knossos and from Rajasthan to China

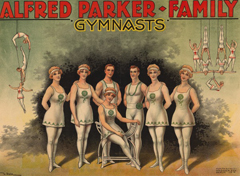

Acrobatic training is linked to mastering a vocabulary in order to construct sentences and then sequences accompanied by appropriate music. From Babylon to Knossos, and from Rajasthan to China, the objectives are identical, and over the centuries and with successive enriching elements of an almost universal practice, an intuitive diaspora has built up around a shared repertoire. The acrobat's trajectory is similar to that of the gymnast, but they become closer and sometimes merge from the 19th century onwards, whenever the circus was in search of new elements. The appeal of an artistic career motivated gymnasts to model their practice as acts, acquire costumes and become circus artists.

On January 1st 1818, a military man of Spanish origin, Colonel Amoros, used a municipal fund to set up the first French establishment for physical education aimed at school children. He created a theory for his teachings and published his treaty for physical, moral and gymnastic education in which he defined gymnastics as "the reasoned science of our movements and their relation to our senses, our intelligence, our morals and the development of our faculties." The Amoros technique followed in the footsteps of Johan Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827) and Pehr Henrik Ling (1776-1839), but developed work on apparatus, beams, crossbars, octagons and ladders as well as human pyramids. By taking an interest in these interlinked and group constructions, he approached community practices which were informally close to spectacular acrobatics.

Group forms

Going beyond the limits at collective celebrations, whether votive, carnival or funereal, is often the occasion for integrating acrobatic forms, sometimes on a very large scale, in the very heart of the city. In 18th century Venice, carnival was always an intense moment for the citizens of the republic and numerous demonstrations took place with the participation of the entire community. The Forze d’Ercole, a competition which, since the Renaissance, has set two rival factions, the Nicolotti and the Castellani, against each other, is a challenge to construct the highest possible human pyramid on rudimentary stages which were sometimes just planks assembled on top of barrels. Representatives from the two main districts of Venice would face each other on St Mark's Square, but also in other places throughout the city and sometimes even on the Grand canal, using barges that were big enough to hold tens of people in order to create spectacular human scaffolding. They were accompanied by musicians, flutes, drums and trumpets, which played in rhythm to the different stages of construction. The two rival groups faced each other in serious battles, mainly on the Santa Barnaba Canal up until the first years of the 18th century. The first steps of the pyramid were supported by wooden beams placed on the shoulders of the bearers and enabled some stability for the base of the construction. In most graphic portrayals of the Forze d’Ercole, there is a reference to the mountains that border the Straits of Gibraltar and which symbolised, in ancient times, the border between civilisation and an unknown, dangerous world. The painter or engraver has placed a thick cushion at the foot of the pyramid, the ancestor of the modern protection mattress sometimes set up under apparatus suspended above the ground. The painters Balthasar Nebot (1700-1770), Francesco Guardi (1712-1793) and Antonio Canaletto (1697-1768), as well as numerous anonymous engravers have immortalised the Forze d’Ercole, thereby showing their importance and their unifying dimension in a society open to the world.

Catalan Games

These Venetian games also recall the castells Catalans, a traditional demonstration in that part of Spain that saw elaborate human constructions made of six to ten levels. Their origins are unknown, but these "castles" could derive from small human towers built at the end of an ancient dance in the Valencia region and southern Catalonia at the beginning of the 18th century. The desire to create higher and more complex towers led to the technique being developed until it became perfectly autonomous and an activity in its own right. To structure this symbolic and group practice, the participants formed colles castellerres, to train and to create new ways of building towers. To "validate" a tower, a child has to climb up to the top and raise an arm to signal the end of the demonstration.

The golden age of castells lasted from the mid-19th century to the first half of the 20th century. The actuacions castelleres, literally castle representations, were regularly practised in southern Catalonia, in a triangle formed by the cities of Valls, Tarragona and Penedes. Massive rural migration in the early 20th century weakened the practice of castells, which also faced competition in the shape of popular sports. In spite of renewed interest during the inter-war period, it was not until the 1980s that the castells found favour once again among participants and audiences. New figures were created such as the "nine of eight" and about sixty associations, or colles were created in the decade that followed, in other regions of Spain such as the Balearic islands, but also in Brazil, Canada, France, Chile and China. An ancestral and popular acrobatic practice, the castells were listed as a Unesco intangible cultural heritage on November 16th, 2010. The castellers' motto of "strength, balance, courage and wisdom" resonates strongly with the qualities of the practice of acrobatics since their origins and although it is difficult to consider the castellers as "true" acrobats, they remain famous for their physical training and commitment.

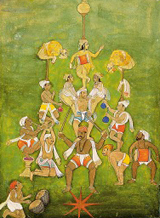

Dahi Handi

Occasional acrobats, the castellers are similar to the thousands of participants who gather each year in hundreds of teams to celebrate the birthday of the god Krishna in the immense Mumbai metropolis and the entire state of Maharastra. The aim was to build a pyramid high enough to enable the acrobat perched on the top to break an earthenware pot suspended from a great height filled with milk, water, butter, yoghurt and fruit. The Dahi Handi (literally yoghurt pot) tradition is associated with one of the god Krishna character traits, as according to legend the latter used to steal pots of yoghurt and butter when he was a child. Drawn from the Mahabarata, which along with the Ramayana forms one of the two great epics of Hindu mythology, the anecdote is now an opportunity to build pyramids in a festive and popular event that has political implications.

Many elected officials compete furiously and each organise their own Dahi Handi, with prize money that can amount to one hundred and fifty thousand dollars for the winning team that manages to break the earthenware pot and thereby spill the milk, butter and fruit. The participants train for several weeks before the event, and develop construction strategies, which are consolidated through numerous rehearsals. The team members are called govindas and their groups are mandals. During celebrations, they move from one area to another and attempt to break as many pots as possible, tirelessly reconstructing their pyramid. The first levels of the structure need to be solid and the bearers are often massive. The higher up the pyramid you go, the slighter the men become, and a child climbs the human tower before standing at the very top to ensure victory for their team.

In 2012, Jai Jawan Govinda Pathak, a mandal from an area in Mumbai entered the Guinness Book of Records for having formed a 13.35 metre high pyramid, breaking the previous record held by Spain since 1981. The event encouraged several people to evoke the idea of creating an official sport, but there were numerous instant demands that the Dahi Handi maintain its status of street celebration, with an occasional, symbolic and ritual character. The towers are traditionally built in the middle of a dense crowd where the closest spectators spray the participants with water to discourage them, while others chant a ritual phrase announcing the govindas. Tower construction is often accompanied by musicians and dancers who create a parallel event. The festive dimension of the event should not obscure the risks: the towers often collapse, provoking serious injury and even death.

Trained to find the best points of balance and to spread the mass according to the team members, the govindas are more strategic planners than acrobats, destined above all to provoke a participative movement to consolidate a group and confirm collective solidarity.

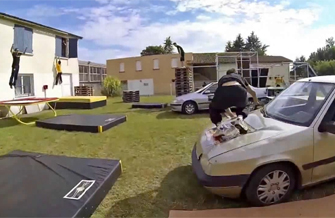

Parkour

At the beginning of the 20th century, a French naval officer, Georges Hébert, developed gymnastic exercises based on the natural capacities he had observed during his time in Africa spent with patrols and hunters. Back in France, in Reims, he founded a method based on the natural abilities of his pupils and which evoked the fundamentals of walking, running, jumping, climbing, swinging, crawling and swimming etc. He implicitly renewed links with the roots of early acrobatics, based on the observation of animals crystallised through imitation rites and gradually transformed into a repertoire of figures and intentions. His technique became the basis of the French army military training. Inspired by his work, a Swiss architect created and developed a series of obstacles aimed at testing strength, speed and endurance in soldiers. It was called the obstacle course.

At the end of the 1980s, David Belle, an athlete inspired by his father's experience in terms of physical training, and who wanted to experience another approach to movement, integrated the principles of the military obstacle course but transcended it with a freer approach, without losing the rigorous training method. With a group of friends, Sébastien Foucan, Châu Belle Dinh, Williams Belle, Yann Hnautra, Laurent Piemontesi, Guylain N'Guba Boyeke, Malik Diouf and Charles Perriére, he developed a system of rules and codes to construct an original vocabulary that led to the development of a form of urban acrobatics. The city was revealed as a formidable terrain to explore, and for the price of an intensive amount of training, was available to these heirs of the former wood runners as a formidable "parcours" (course). In 1997, invited to perform in public, the group decided to present themselves under the name Yamakasi, a term from Lingala, a language spoken in the Congo, which means the fusion and strength of the spirit in the body.

Sébastien Foucan suggested describing their approach to movement as "The art of moving." The group separated shortly after, and Hubert Koundé, a friend of David Belle, suggested that he develop the term "parcours" towards "parkour": from now on, the training method developed by David Belle would be known by this name, and its followers were know as traceurs. The parkour became popular in the 2000s and benefitted mainly from the impact of the film Yamakasi produced in 2001 by Luc Besson, after he had used traceurs in his film Taxi 2 in 1998. In 2003, the documentary Jump London with Sébastien Foucan used the term freerunning rather than parkour in order to speak to an Anglophone audience. Parkour, the art of movement and freerunning, beyond differences linked to the personality of their creators and followers, identify both a practice and an art. In 2006, the Martin Cambell film Casino Royale integrated a parkour sequence with Sébastien Foucan and marked a turning point in the perception of the discipline. Mastering the parkour means intense and rigorous training and its founder explicitly claims warrior origins to qualify his method of acquiring a demanding technique that may be dangerous for ill-prepared followers. Concentration, reflex control, ability to apprehend distance and a sense of space and the void are a few key elements for understanding and mastering jumps, impulsion and propulsion. Urban acrobatics, a symbol of freedom and a means of expression, the parkour is undoubtedly above all a life principle in which the body and mind train to overcome obstacles and barriers, whether metaphoric or real. It is a way of overcoming one's fears and transfusing this new strength into daily life.

Celebrating

In Taiwan, for certain Taoist funeral ceremonies, the family of the deceased sometimes call on acrobats to accompany the departed soul on its final journey. The ritual can take place in the city, in a square or a car park among cars, indifferent passers by, and the incessant city noise. There is no audience and yet the celebration looks every bit like a performance. To the uneducated eye it looks like a troupe of tumblers has decided to perform outdoors without a predetermined space, with the sky, sun, clouds and rain for décor. A juggler spins a straw hat on a parasol bereft of silk, showing its fragile structure, metaphorically illustrating the rotations of the sun… Acrobats leap over hoops placed on a simple wooden table, and their jumps symbolise doors crossed by the deceased's spirit to achieve the final destination on their journey. A balance artist stands on his head and uses his hands to remain upright while spreading his legs apart to form a symbolic receptacle, thereby illustrating with his body the secular ding, the bronze urn of ancient dynasties indispensable to the celebration of the cult of the ancestors.

These acrobats have ancient skills, and are used to theatre stages and performances for tourists, but are also capable of contributing to ancestral rituals. The human pyramids from Venice to Mumbai, cement communities, while the traceurs imagine and experience the city differently. They all embody acrobatic movement well beyond the limits of the circus, and grow stronger throughout he centuries, putting down roots in the social fabric, and confirming themselves as a powerful vector for the collective memory.