by Pascal Jacob

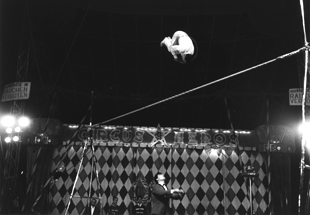

The tensioned wire has an intrinsic flexibility, caused in particular by the power which is required for a maximum tension, and which is indispensable for sliding and jumping. This rebound energy is found in the ancient practice of cuerda dinamica, a technique widely developed in Colombia where it started as a street game and has gradually transformed into an acrobatic technique. The rope-walker José Henry Caycedo Casiera, who trained at the Académie Fratellini, presented this art form which is rare in the West at the 29th Festival Mondial du Cirque de Demain, coupling his acrobatic performance with a theatrical context through the development of a strange leaping faun character. Trained at the National Circus School of Montreal (l’École nationale de cirque de Montréal), Raphaël Fréchette designed a unique apparatus with two horizontal and parallel elastic straps, an original device giving him a range of possibilities for rebounds, both dorsal and ventral, but which also opened the way to a comical narration of the performance.

A more classical duo, trained at the Pyongyang acrobatics school, combined sets of fans and jumps on the bouncing rope, landing upright on a particularly unstable apparatus, reinforcing the choreographic dimension of the sequence of moves carried out as a solo or duo. The precariousness of the fans is counterbalanced by the power of the jumps; the precision of the gestures like the landings creating a vibrant contrast in the exercise of a very physically demanding discipline. A dimension also revealed by the Chinese acrobat Cong Tian, a solitary virtuoso in bouncing rope and a real rope-dancer in the most exact sense of the term. On his rope, the artist completes a succession of gestures and movements that eventually make us forget the apparent simplicity of his apparatus. The two young members of the Shanghai acrobatic troupe who performed in Paris in 2015 at the Cirque Phénix have developed a work at the crossroads of Asian acrobatic research: mixing crossings and individual jumps with transitions and crossings as a pair, they offered another dimension for a technique often practiced as a solo.

Bouncing

The recent discipline of slacklining, a freely practiced contemporary cord dance that starts with a simple flat strap hooked between two trees, is closely tied to the principles of tension, elasticity and bouncing that we see on the steel cable and is an adaptation of the dance on a brass wire but on a flat strap. It is an innovative technique created in 1979 by Adam Grosowsky and Jeff Ellington at the Evergreen State College in Olympia, capital of Washington State, followed by one of their fellow students, Brooke Sandahl. Accustomed to balancing on chains and cables, they opted for the nylon strap because of its flexibility, simplicity and manoeuvrability.

Very quickly, this practice radiated throughout the Californian campus and beyond. The slackline developed with a specific typology according to the distances and the height at which it is practiced. If the crossing is complicated by tricks, jumps, balances and half-turns on a strap from 5 to 30 meters long we refer to is as trickline; longline if the distance is more than 30 meters and, from a height of 5 meters from the ground, the term highline is preferred. The strap is between 28 and 50 millimeters wide, fastening and stretching almost anywhere, by a system of hauling and pawls. Slacklining is a community-based discipline thanks to its approach and the ease of its practice and this contemporary apparatus shows a resurgence of the bouncing rope dance, which was very popular in South America and Asia, and especially Korea since the first century AD with the practice of the Jultagi, born in the kingdom of Silla (57-935). In the 1930s, the Indian Kannan Bombayo toured the world with a stunning act on a thin cotton cord of spectacular elasticity stretched three meters from the ground. However, the Frenchman Li Suang, in the 1960s, or the Portuguese Lorador Junior, twenty years later, not to mention the Colombian José Henry Caycedo, in 2009, have all shown a mastery of this technique that oscillates between balance and propulsion: yet another possible outcome from the multi-faceted apparatus, the rope.