by Jacques Richard1

In the 1950s, when I mentioned to Henry Thétard the acts I’d discovered at Medrano that I thought were sensational, he sarcastically put my enthusiasm into perspective: “Before 1914 was the time to go to the circus”.

Before 1914 was the time of his youth and now, like Thétard, I also tend to favour another pre-war period in my own memory, pre-1939. I lived in a small provincial town, Dax, and my parents, intellectuals who didn’t look down on the circus, tried never to miss the tents when they passed through. They would take me with them, of course, and the first circus show I attended was the Zoo Circus, where Alfred Court introduced the unforgettable mixed group he had put together. That magnificent mingling of lions, tigers, polar bears, brown bears and Great Danes has gone down in history, but I must have been three at the time and the only thing I remember from that matinée performance is the giant dogs in a cage and the acrid aroma of the wild beasts, which has stayed with me and, from that day on, became synonymous with the circus for me.

Another smell that transports me in the same way is that of the stables, the prerogative of a medium-sized big top with a serious reputation back then. It was there that, as a child, I had the opportunity to learn about the circus, but one without wild animals, where the horse was king.

The Cirque Bureau stopped under the ramparts in the Place Saint-Pierre every year, proud to justify its slogan: “The circus without bluff”. A respected circus, it was run by Anna Ferroni and her husband Jules Glasner. I would later learn that Anna was the granddaughter of Jean Bureau, founder of that particular circus, and that her husband was descended from Louis Delafioure, who ran a monkey theatre in the late nineteenth century. Every season they would present a large riding school, both “free style” and haute école”. The couple who ran the circus were always named in the programme with a respectful “Madame Glasner and Monsieur Glasner”, no first names. Decked out in feathers, Madame Glasner was always in a long dress, sometimes grey lamé, in her haute école sulky, an act I was happy to see again, convinced that this elegant woman had the innate gift of class.

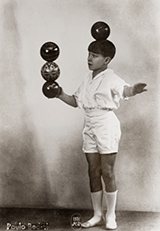

In 1936, the programme announced: “Paolo2, the greatest juggler of our time” and I had a vague feeling (I was seven) that I was applauding an exceptional artist. I enjoyed “The eccentric Moustier Brothers”, unaware that I would come across Louis Moustier forty years later at the school founded by Annie Fratellini and Pierre Etaix. Paolo was none other than Louis’s brother-in-law and I seemed to recognise him in the Bedini-Tafani troupe that was also on the programme. It was him, with his brothers and sister Nora, who married into the Moustiers. Since the late Middle Ages, the Moustiers could boast the extraordinary surname of De Dessus le Moustier. All this left me wondering.

The war came to an end and, right away, the Cirque Bureau returned to Dax, still without any bluff, but now with lions tamed by Ivanoff. The riding school seemed smaller, but Madame Glasner was still the star of the show – in her long dress and on her spidery sulky – and the years had not altered her grace. I remember knocking on her trailer door to give her a large bouquet of hydrangeas from the garden. It was the first time in my life that I dared to speak to a circus woman like she was a mere mortal. Anna Glasner died in 1958 and would be survived for four years by her husband.

The programme doesn’t specify the date, but it was before 1936 that a circus with a huge menagerie stopped in Dax for the first time: Amar, then at the peak of its popularity, with polar bears, lions, tigers and sixteen elephants that paraded through the town. I was amazed, but what I remember even more clearly was Germain Aéros, the drunkard acrobat, who seemed to me to possess the gift of exceptional humour. If the programme wasn’t there to confirm it, I would have forgotten “Le Jockey d’Epsom par les deux Chotachen”, one of whom must have been Chotachen Courtault, whose role as a teacher left its mark at the École Fratellini-Etaix. A year later, in 1937, “Medrano voyageur”, “Le Cirque de Paris”, was in Bayonne, and my parents took me. The whiff of a distinguished circus floated on the air under the big top. It struck me that if, at Amar, it was the multitude of wild animals that counted more than anything, at Medrano, the elegance of the presentation prevailed, with Vojtech Trubka’s tigers. This disciple of Alfred Court was very chic in white and the movements performed by his tigers created real harmony. Top of the bill were Paul, François and Albert Fratellini, and, as far as I was concerned, they lived up to their considerable reputation. Medrano sacrificed itself to the fashion for champions in vogue in the circus at that time, with Jules Ladoumègue, as Bureau would do in 1938, with Charles Rigoulet “The strongest man in the world”, and Pinder with the Tour de France’s ace cyclists in 1937 and the boxer Marcel Thil in 1938, on the same programme as the Saut de la mort des Clerans, whose tragic end would come at the Gaumont Palace in Paris on 7 July 1946. The Léonards, Cirque Pinder’s clowns, brought with them a good mood that was infectious. I remember, in particular, the “Pompiers de Nanterre”, who splashed plenty of water around.

In the spring of 1939, the four Bouglione brothers’ big top stopped off in Dax. My parents were busy so I had to content myself with visiting the menagerie. The well-disposed clientèle were informed that a ticket for the zoo allowed them to attend the circus directors’ meal, every day at noon in their caravan. Was it a joke? The fateful hour had long since passed, but an enormous TV set was set up, through the caravan door, to the admiration of the crowds. At 800 km from its Paris transmitter, the TV obviously didn’t work.

That was the last day of my pre-war period. Everything I had glimpsed about the circus during my childhood left a big impression on me, through the emotions of the show, the happiness in everyone’s eyes and the strangeness of this travelling and almost parallel universe. The fanfares of the “Tchéco” orchestras, as they were known at that time, the indefinable accents, the smell of the circus, whisked the little inexperienced Frenchman that I was far away, convinced that travelling people were a different species. My memories are imprecise and incomplete, but the immediate appeal I felt remains vivid. No trace of thoughtfulness. The ring had seduced me. Once and for all I was won over. I had chosen my side. No need to justify myself. When it came to thinking about the circus, I would have my whole life for that.

1. As told to Marika Maymard by her friend Jacques Richard (Dax, 9 August 1929 – Paris, 9 February 2018), commentator on the circus and cinema, for posthumous publication. Published on page 44 of Cirque dans l’Univers n°268 in the first quarter of 2018.

2. The author is referring to Paolo Bedini, inspired by Rastelli, adopted as a child by the Bedini-Tafani family.