by Magali Sizorn

Inciting curiosity and provoking fear, sharp intakes of breath or shouts, sensational attractions combine entertainment with sacrificial demonstrations.

Searing intensity and strong emotions

Hanging from a trapeze, Zazel has just finished her flight across the room, having been shot from a cannon in a cloud of smoke. It is 1880, at Barnum's, and the act invented in 1875 by "Prof Farini" (real name: William Hunt), was extremely successful. This woman-obus act was a reminder that the circus show acquired legitimacy through spectacular innovation (Hodak, 2006). At Astley's, the acrobats' flights or crossings attached to a pulley, attracted an audience partial to new types of entertainment.

The attractions, which broke up the rhythm of the show with their lightning speed (a dive, a loop, or a cannon exit), spiced up programmes and showed how the circus borrows on multiple levels. By offering the new and the "even-more" the circus recalled the emerging values of sport. Proximity to the fairground universe was also particularly perceptible in the attractions, for which the key word was rivalry. The Hercules strongmen of public squares were transformed into "cannon-men" carrying the weapon on their backs and remaining immobile until the cannon was shot. The torpedoes, or human arrows, were propelled by giant crossbows until they tore through sheets of paper, while men- and women-obuses were projected above the stalls from the end of the 19th century onward.

These "thrill acts" defied reason in performances as random as they were hazardous. Thus the men- and women-obuses passed through flaming hoops to land in the arms of a catcher on the trapeze, and sometimes passed by each other. In spite of careful preparations for the acts, machine settings were unreliable and accidents were not infrequent. The victims of paralysis and death were numerous, and the performers in star-acts were sometimes different acrobats with the same name. This is illustrated by this anecdote told by Rolph Zavatta (1963, quoted by Catherine Zavatta, 2001, 30): "This exercise got through a lot of people because of small accidents of which the acrobat was often the victim. I knew five of them, and having used up all the Miss Curtises, one evening we had to replace the last, unavailable Miss with the circus's accountant-driver, Albert Neufcoeur, "Bébert".

Machine-proof

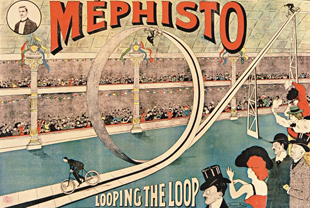

While at the end of the 19th century mechanised fairground attractions appeared, the circus also became a place of technical innovation where the rapport between nam and machine was exhibited. The loop-the-loop, invented by the American (James Smithson, aka Diavolo), was presented in France in 1900 at the Rancy circus. Riding a bicycle (later replaced by a motorbike and then a car), he rode onto a springboard which was raised to create a circle, inside which, thanks to centrifugal force, Diavolo performed a "perfect loop". Following 1850s trapeze exercises under hot air balloons from 1930 onward, acrobats would hang from fake airplanes under circus cupolas, or even from real helicopters. In this way Andrée Jan flew over summer beaches on a trapeze in the early 1950s (Jan 1953).

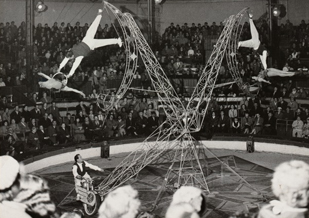

Generally, machines generated movement, acceleration, propulsion and catapulting. Acrobats had to adapt, remaining sheathed during flight, or walking on, or in, the wheel, so as not to fall.

These exercises were sensational in their capacity to create thrills, and yesterday's acts continue to move today's audiences. This is demonstrated in performances of the "human arrow" act or the death wheels that can now be readily found at the Arlette Gruss circus (the Varegas duo in 2012), at the Cirque du Soleil (Kà in 2003 and Kooza in 2007), in contemporary shows such as Super Sunday by the Finnish Race Horse company, and in the street, with the likes of La trilogie du temps by the Marseille circus studios.

The fascination with technical progress is definitely not the same today. In traditional circus programmes, taking up an act again demonstrates a return to sensationalism, while other genres question the dramatic use of a race for achievements, and incertitude in the confrontation between man and machine.