by Pascal Jacob

When the aerial choreographer Piotr Maestrenko created Les Cigognes in Moscow in the mid-1980s, he chose to incorporate the landing net into the staging of a flying trapeze act inspired by an old Russian legend. The supple net allowed a combination of falls and rebounds by assimilating them to a second level of acrobatic language in parallel to aerial developments. The transformation of a utilitarian object and a powerful stage element transcended by the light, provided a striking contrast with the banality of a simple stretched net.

This ability to interpret an apparatus beyond its appearance and its accepted use is particularly obvious with the trampoline, more willingly identified as a training support or grounds for competition. The Les Mains, les Pieds et la Tête Aussi company, founded by Mathurin Bolze, explores another rapport with space and verticality. The show, Fenêtres, is, as such, a veritable deconstruction of the apparatus, rendering it invisible, and turning it into a simple device for flight and for bouncing off unexpected surfaces. The stage device, with audience incorporated, placed in front of a "window" reinforces this dimension of turning things upside down, and weightlessness, and provides the acrobat with a diversity of supports and multiple surfaces to work with.

This questioning of the rebound is illustrated in the "trampo-mur" discipline, which re-appropriates the apparatus in the service developing the technical vocabulary. The show by The Collectif AOC, La Syncope du 7, directed by Fatou Traoré, incorporates a trampoline into its stage design for a variation on the theme of imbalance, a principle accentuated by the screens, with openings pierced in them, providing multiple possibilities for escaping and re-appearing. Le Vertige du Papillon directed by Philippe de Coen, also works with trampolines incorporated into the stage design. In another register, the Flip Fabrique company makes the "trampo-mur" act the bravura passage of the show and the prelude to its finale.

This idea of flight and rebound, suggested by the Hungarian teeterboard and the Korean plank, which are old techniques inspired by the principle of counterweights seen in the catapult and trebuchet, is still a source of creativity, whether in terms of movement or the apparatus. Odilon Pindat, trained at the National Centre for Circus Arts in Châlons-en-Champagne, created his Trébuchet by revisiting the imaginary Middle-Ages warrior, and incorporated the Race Horse company into the show, Super Sunday. This unique apparatus finds its ideal place in a sort of catalogue of out of the ordinary performances, such as the Death Wheel, and corresponds perfectly to the desire to revisit thrilling "machines" that have made the circus remarkable since the end of the 19th century.

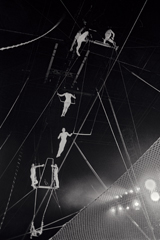

The La Meute company does this very thing by alternating between the Russian cradle and the teeterboard, playing with these two apparatus as solid grounds for multiplying exits and spectacular figures. The Russian cradle is an apparatus frequently used in Fanco Dragone's shows, in which the presence of water encourages spectacular exits and gives additional lightness to figure sequences. The Skokov company, comprising almost exclusively female acrobats dressed in long floaty skirts, ads another dimension to a discipline often seen as essentially masculine.

The Korean plank is now common both in training centres and in the imaginary universe of contemporary acrobats, and is a source of inspiration for technical, choreographic and theatrical sequences. The apparatus, which can be practised alone or as a duo, provides interesting possibilities for performance, but is also a formidable tool in developing impressive figures. The appeal here lies in a form of simplicity, and a "facility" of access, which does not in any way mask the skill of the artist, in turns both flyer and pusher. This duality, which needs neither pedestal nor the weight of the partners to increase the impact of the push, is fascinating in its rigour and purity. This modest appearance and use probably counts a lot for its success and the recognition of an apparatus, which is increasingly appreciated by circus students. The Baskultoo duo, the Cheptel Aleikoum and the Fanfare Circa Tsuïca, mostly constituted of former students of the National Centre for Circus Arts in Châlons-en-Champagne, demonstrated that the rudimentary aspect of the plank could transcend itself by different rapport with space and its propulsion faculties: a musical and humorous dimension blended with a series of acrobatic moves creates a joyful and dynamic sequence, in which the apparatus becomes both the grounds for the piece and its support.