by Pascal Jacob

Some people sometimes consider the circus as an avatar of magic and it is clear that the notions of attraction, surprise, wonder or terror can constitute spectacular bridges to forge intuitive links between forms. There are many correlations between acrobatic disciplines and certain principles of illusion, but it is also in the allegory of floating or flying bodies, suspended or dislocated as "by magic" that analogies and shared references must be identified.

The circus appreciates the emphasis and superlatives to define itself, but it also combines an exacerbated reality with ever-expanding physical limits. This combination of intentions works well with magic and the squire and entrepreneur Philip Astley, a magician himself, offered his audience spectacular tricks at the end of the 18th century, Philosophical Amusements1 or the tricks of Magie blanche2, as, a century later, in 1884, Buatier de Kolta will be presenting his Magic Die at the Cirque d' Été.

From the very beginning, the circus has always appreciated the notion of effect, whether it is in a visual or sound form. The drum roll, real or symbolic, the creation of a palpable tension as feats or tricks are performed, are all part of the same desire to surprise. Since the 19th century, the circus has also developed an immoderate taste for the animal on display, tamed if not trained and offered to the admiration of an audience that is always fascinated. This duality of form and substance contributes to forging solid links between the circus and illusion to such an extent that magicians or prestidigitators are often spontaneously considered to be emblematic figures of the circus! However, when it is performed in a 360-degree playing area, the ring can be very challenging for magic.

Subterfuges

Anything related to disappearance, concealment or levitation is made all the more complex by the omnipresence of spectators, the absence of arches or stage cages and the impossibility of protecting pits and traps by digging under the ring before erecting the big top! In England in the 1920s, The Great Carmo, a magician accustomed to the classical stages of theatres and music halls, nevertheless offered himself a circus where, in addition to a succession of traditional acts, from trapeze artists to trained lions, he presented some of his great illusions. At the same time in France, Carrington offered "the most bewildering show of the century". The magician multiplies the sensational attractions, proudly announces on his posters "What the eyes see and what the mind cannot believe" and claims to play with the supernatural. The Hungarian-born magician Franz (Ferenc) Czeisler (1916-2016), universally known under the pseudonym Tihany, began his career in 1930 in Montevideo as an assistant to Blacaman3, a Calabrian who became a fakir and an animal tamer. He himself performed a fakirism act, notably in the ring of the permanent circus in Budapest on his return to Hungary. Invited to Brazil in 1953, he found a territory in South America that was up to his standards and it was there that he created the Circo Magico Tihany, a sumptuous travelling tent whose shows were more like revues, but where magic was still present.

Magic in the ring

Many magicians chose to adapt their illusions to the demands of the circle and performed successfully under travelling tents despite the sometimes-frenetic pace imposed by the tours. The Frenchman Al Rex performed in the 1960s with his own big top, a pioneer in inflatable structures, and inspired magicians like Jan Madd and Yanco.

The Sabine Rancy circus regularly called on magicians in the 1960s and 1970s, including Jan Madd and his doves in 1972, Tao Minh and Al Rex in 1973 for the reenactment of La Féérie au Népal created in 1968 or the Jolsons in 1974. The latter literally "scoured" the French rings during the 1970s and 1980s, with a renewed Trunk of India and several large illusions conceived as original variations from a classic canvas.

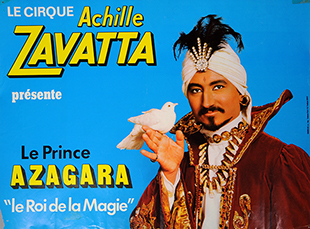

Whether it was Jack Kodell at Medrano in 1956, Mireldo at Pinder in 1960, the mentalist duo Myr and Myroska at the Amar circus in 1971, Yanco and Azagara on the Achille Zavatta circus stage or under the cupola of the Cirque d'Hiver in the 1980s, not to mention Borra Sr and Michel de la Vega in the Jean Richard circus ring respectively in 1972 and 1981, or Charly Borra at Knie in 1990. All take the risk of working in the heart of an open space and without real possibilities to use the usual codes of concealment. Today, the Ukrainian Voronin is happy to perform in a circus ring, as in 2004 at the Salto Natale4 show in Zurich. He colours his performances with humour, alone or with improbable partners like Joe de Paul or Peter Pitofsky, hiding a formidable virtuosity under the guise of a clumsy Mandrake.

Adaptations

In 1957, the Council of Ministers of the Soviet Union founded Soyuzgoscirk, a central and all-powerful body for creation, production and distribution, entirely devoted to the aesthetic and technical transformation of circus art. Eager to explore all the artistic fields related directly or indirectly to the circus arts, the directors of this new institution associate magic and illusion with their catalogue of performances and promote the domination of the Kio dynasty. The first of the name, Emil Teodorovich Hirshfeld "Renard" was born in Germany on the 11th of April 1894. His two sons, Igor and Emil, succeeded him after his death in 1965 and performed around the world until the early 2000s. For them, a ring with traps was designed at the New Moscow State Circus in 1971, a discreet and ingenious device that makes it possible to create unexpected apparition and disappearance effects, even in the middle of the ring. In 1960, Emil Kio and his troupe performed the second half of the Schumann circus show, a principle that was also well established in Moscow, where the richness of his repertoire gave him the opportunity to present an entire programme of illusions.

It is indeed a question of creating a show within the show, while respecting the performance codes of the circus. The integration of illusion into the very body of the spectacular narrative, following the example of the show Kà, directed by Robert Lepage for Cirque du Soleil in 2004, further changes the status of magic in the circus by multiplying references to practices inherited from the 19th century. Since its foundation in 2001, Compagnie 14:20 has been exploring these natural porosities and ties by creating strong shows and fostering artistic and technical collaborations with, among others, Cirque du Soleil to create a permanent show in 2020 where magic will be both a source and a fundamental purpose for several performances. Etienne Saglio or Yann Frisch within the companies Monstre(s) and L'Absente in turn weave subtle stylistic correlations between circus and magic by drawing from the repertoire of classical forms a sharpened inspiration to invigorate their imaginary world.

1. Steve Ward, 2018, p. 77.

2. Idem p. 48.

3. Born Pietro Aversa in 1902 in Castrovallieri (Calabria, Italy).

4. Produced by Rolf Knie the show Salto Natale is directed by Guy Caron.