by Priam Pierret

The diabolo, a traditional Chinese variety game and art, has been present in the streets and acrobatic theatre for two millennia, most often practiced by young girls.

Vague origins

A recreational object that came from China between the 1st and 11th centuries, it is called a kouen-gen, or "vacuum apparatus", like the air that comes out of the two moving side discs. In the aftermath of the Revolution, the first kouen-gen, brought to England, crossed the English Channel and took the name "devil" in reference to the intense and acute whistling, like "a devil's racket", that the air produced on the rotating slits.

The diabolo fashion came and went during the 19th century, with the appearance in circuses of the first European diabolist artists. In 1906, the Franco-Belgian engineer Gustave Philippart (1861-1933) reinvented the object. He gave the caps their conical shape and made official the name diabolo, a play on words between "devil" and the Greek verb "diabállô" dia - bállô, literally "throw across". The game becomes increasingly popular through regular competitions. But many accidents cause it to be banned in most public spaces and there is a significant loss of notoriety.

Swiss precision, German quality, Asian plastic

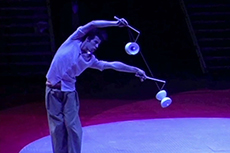

At the end of the 20th century, the best diabolos were manufactured in Switzerland and Germany, moulded in resistant and undeformable elastomeric materials. The few passionate enthusiasts or diabolist circus artists develop new figures thanks to technical innovations, including shorter sticks made of metal or carbon, with a wire coming out at the end, which guarantees better stability in the air and the creation of many stick release tricks or suicides. In addition, a very precise balancing and synthetic twines allow rotational speeds of more than 2000 rpm while perfectly maintaining the starting axis – by balancing the gyroscopic forces. This allows figures with two diabolos beyond the simple carousel – circular movements in opposition of the two diabolos –, such as the famous whirling or the capture of the carousel in a large string loop.

In the 1990s, these new repertoires were then put into books and videos such as Diabolo Folies, which revived the vogue for diabolo in Europe, both as a game and also as a genuine circus discipline, as an art of juggling. Japan is innovating with the use of plastic caps to reduce friction between the caps/string and the ball bearing to prevent deceleration. The Japanese website DiaRhythm (2001) features videos of new figures, and the Japanese artist Ryo Yabe is the first diabolist to win the International Juggling Association competition (2002, Junior category).

Global diabology as the impossible is annihilated

In France, in 2002, engineering students Priam Pierret, Jean-Baptiste Hurteaux and Sylvestre Dewa, brought together the most innovative French diabolists, including multi-recordman circus artist Tony Frebourg, to create Diabology, the first DVD dedicated to a compilation of new figures with one and two diabolos and the first repertoires with one diabolo in vertical axis (vertax or excalibur), three and four diabolos in the air – with the siteswap theory adapted from ball juggling –, in passing, in duo with five and six diabolos, and especially, with three diabolos in the string, something which seemed impossible until then. In Germany, at the same time, Lena Koehn enriched the repertoire with two and three diabolos and Roman Müller and Petronella von Zerboni, directed the first vertax number within the duo Tr'Espace.

Internet resources, juggling conventions and the organisation of freestyles and battles (forms of competitions based on hip-hop culture), have helped bolster a growing community and paved the way for new explorations: body figures and integral releases – held by the centre of the string with the two sticks thrown in rotation – to a diabolo, transposition of the one and two diabolos repertoires respectively to the two and three diabolos repertoires, vertax to two diabolos, figures to four and five diabolos in the air and four diabolos in the string, and passing eight diabolos as two diabolos.

In Taiwan, where traditional Chinese culture meets Japanese modernity and where diabolo is a compulsory sport in school, the M.H.D. collective trains young diabolists at the highest level like Lin Wei Lang, also known as William Lin. Several Asian collectives were then created. In many countries, innovative diabolists contribute to the expansion of the repertoire, as in France, self-taught artists such as Guillaume Karpowicz, Etienne Chauzy, Robin Spinelli, Alexis Levillon, perpetuate French-style innovation. In 2010, Nico Pires, based in Hong Kong, succeeded in uniting about one hundred global diabolists around the Planet Diabolo project, which brings together these new repertoires in several forms of compilations. The community continues to see its repertoire grow: one and two diabolos in indiana (two sticks in one hand and whipped manipulation), two galexy diabolos (one diabolo in the horizontal axis and the other in the vertical axis), three and four diabolos in the string, self-starts for five diabolos in the string and six diabolos in the air, figures in passing for five and six diabolos, starts in passing for nine and ten diabolos). In fifteen years, the total repertoire of the discipline has grown from around one hundred figures to several thousand, producing an ideal that seemed unattainable.

Beauty, simply beauty

The extraordinary complexity – a very strong entropy – of the diabolist system / sticks / string / diabolos, which underlies the richness of the discipline's repertoire, is certainly unique in the circus arts discipline panel. Faced with such a large corpus, most established professional artists find it useless to update themselves to reach the famous "wow" effect expected by the public, a little lost by the speed of the movements. We therefore find ourselves in this absurd situation of a circus discipline whose technical limits of the repertoire are maintained by a large community of young enthusiastic amateurs and not by the best professionals. With one exception, the case of Tony Frebourg: a professional for nearly twenty years, he continues to lead the way in aerial juggling with four and five diabolos. Other rare professionals are exploring new paths in the contemporary circus movement. They combine dance, acrobatics or magic or sublimate the simplest gestures with millimetric choreographies to make them appear in a new light. Thus, Guillaume Karpowicz integrates micro-throws and movements of a single diabolo on its string into a minimalist jerky gesture of extreme precision, creating an absolutely new graphic effect, which is simply of the utmost beauty.