by Erik Aberg

The history of object manipulation naturally merges with human history, and even exceeds it, since some animals, such as great apes, know how to use tools. It is possible to define, by successive reductions, the scope of this catch-all concept. It is presented as a "transparent" manipulation as opposed to the "opaque", occult, manipulation of magic. It describes itself as "virtuoso" and "spectacular and/or artistic", which amounts to excluding certain expert gestures such as the throwing of fishermen with hawks, hunters with boomerangs, the handling of pizza dough or the "juggling" of football champions.

And, within the artistic genres themselves, it is still necessary to exclude the puppet, the instrumental playing of the musicians, although, diverted from their primary function, all these manipulations can also emerge from the juggling process. Finally, in order for the word to correspond as closely as possible to the meaning, even a little fluctuating, that circus artists give it today, it still has to be distinguished from juggling, in other words from the strictly periodic manipulation of thrown and caught objects. The manipulation of objects, which has always been the predominant method compared to juggling, is therefore not periodic. It may involve a throw, the throw of a diabolo, for example, or not, in the case of the yo-yo or contact juggling. It can use a single object in one piece, a lasso, or in several parts, such as a devil stick, or several objects such as cigar boxes or swinging clubs.

It can be broken down into families of movement, for example, according to whether the contact between the hand and the object is constant or interrupted. However, it must be noted that, today as in the past, there is no satisfactory classification of practices, which is commonly shared. There would even be as many forms of manipulation as there are types of objects. However, there are hundreds of them! Just have a look at Dominique Denis' Dictionnaire de la Jonglerie: from rugs to dolls, candles, umbrellas and sickles, jugglers have always handled and manipulated the most improbable objects and continue to invent new objects and materials, involving new gestures. However, a small number of object types and some standard practices form a "common repertoire", often quite old. We will focus on them in the rest of this section.

In the Middle Ages, balance, considered here in the limited juggling sense of "maintaining an object in balance" on the body or on another object, is commonly part of the repertoire of "jugglers", namely artists and acrobats who perform at fairs and "minstrels" who work in castles. Medieval iconography includes balance exercises with weapons, and even chariot wheels. This fundamental form of manipulation has been used throughout history: it was particularly popular between 1820 and 1920, before the jugglers focused on ballistic juggling after Rastelli.

An unexpected development in balance appeared in the early 1980s: contact juggling, invented by the American Michael Moschen, which consists in rolling balls over the different parts of the body by controlling their stopping and circulation. Moschen integrates in particular the use of isolation techniques based on mime. He does not call his work contact juggling. This name is taken from a book by James Ernest who described Moschen's work without his consent. In addition, rather than using standard objects (balls, rings, clubs, boxes, hats, etc.). Michael Moschen works with new abstract and geometric forms such as pyramids, cubes, sticks, circles, S-stafs, thus deeply renewing the aesthetics of juggling.

Michael Moschen's works have been copied, if not plagiarised, very often. The S-shape, in particular, has been taken over under the name of Buugeng. Around 2010, Renegadesignlab introduced a new form into the world of juggling, the 8-shaped ring, which was quickly adopted by the contact juggling community.

A lasting Asian influence

From 1820 onwards, with the arrival in Europe of the first Asian artists, and for a century, juggling was based on balance and non-periodic manipulation. Early 19th century engravings show Indian or Chinese jugglers twirling metal hoops on their toes, while maintaining a stick or a peacock feather in balance on their foreheads. It was the Japanese who introduced the accessories identified as the devil stick and the diabolo. The wooden blocks that we now call cigar boxes also come from Japan but were known later (1870-1880).

The diabolo, born in China during the Han dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) was then called Kouen-gen, meaning "which makes the hollow bamboo whistle". It arrived in Europe under the name of flying cone following an expedition led by Lord George Earl Macartney in 1794. In the first decades of the 19th century, when Indian artists arrived in Europe, the diabolo and the devil stick were already part of their repertoire. At that time, we were talking about Chinese bells and Chinese sticks. But it was the westernised names that finally came to the fore: diabolo, formed on the Greek "Dia - ballo", meaning "to throw across", was retained for the string accessory and the stick took the name of the devil stick. In 1905, the French inventor Gustave Phillipart made the first metal diabolos from two cups whose sharp edges were protected by rubber recovered from old tires. The diabolo was then honoured by the German artist MacSovereign.

The object that current jugglers call cigar boxes was born in Japan where it was used for balance demonstrations with wooden blocks. One of the first Europeans to add these wooden blocks to his repertoire was the Frenchman Félicien Trewey. His fame is such that his accessories are called "Trewey blocks". In the 1890s, an American artist named Jim Harrigan began to use them in a number in which he played a vagrant. To be more realistic, he decorates the wooden blocks into... cigar boxes. The name stuck with them.

The Mouth Stick comes from the Japanese daikagura jugglers. Originally, it was presented as a simple drum stick held between the teeth or balanced on the face. The mouth stick takes a special shape to make it easier to grasp by the teeth. One of the tricks performed during the daikagura rituals is to keep a ball balanced at the top of a stick held in the mouth. Another stick is then placed on the forehead in such a way that it tilts towards the ball. By slowly tilting the head forward, the juggler can then pass the ball from the stick he holds between his teeth to the stick in balance.

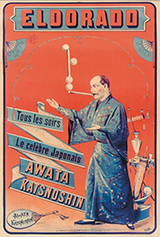

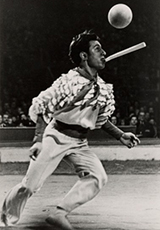

One of the first artists to perform in Europe with this type of juggling was Awata Katsunoshin around 1885. Others followed, such as Ichimatsu, Gintaro Nizihuru and Takashima, inspiring Enrico Rastelli. The latter designed a sensational trick, consisting in throwing rubber balloons into the audience, which the audience sent back to him and which he caught with the stick he held in his mouth. Many jugglers copy this trick, which became very common from 1930 to 1950.

The origin of Chinese plates is unknown, but their existence has been mentioned since the Middle Ages. 2000 years ago, under the Chinese Han dynasty, they were included in the Hundred Entertainments Theory in 108 BCE. Since the advent of the modern circus, the art of spinning a plate at the end of a rod has been one of the juggling exercises performed on horseback. At the beginning of the 20th century, the plates trick was used in the composition of many numbers. For example, a juggler can spin a plate with one hand while juggling with the other with a plate and a pool cue, while keeping a bottle balanced on his forehead.

The German Barny invented the now classic routine of the flying plates, which consists in spinning several balanced plates at the same time on as many rods inserted in a support. The artist gives the impulse for spinning the plates. When they are all in motion, he creates a diversion by performing another trick, such as throwing a series of spoons with a flick of the wrist which fall into as many glasses in a row on a tray. Once the exercise is successful, he returns to the plates display quickly enough to catch them or restart their movement before it dies out.

Other standard objects

Enrico Rastelli is the first juggler to use rubber balloons. He does not "juggle" with these balloons but keeps them balanced on sticks, fingers or head. In his wake, Angelo Picinelli, another Italian juggler, complicates the device: he balances a balloon on a pedestal perched on his forehead and a ring around one leg, while he juggles with one hand with three rings while rotating a balloon on the index finger with the other hand. This balloon number became very common in the 1930s and 1940s, with many variations.

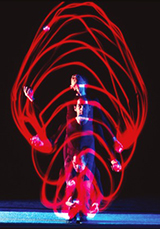

The club, or skittle, is used today, mainly for periodic juggling. But it lends itself to various types of non-periodic manipulations, ballistic in the context of rhythmic and sports gymnastics, graphic with swinging, when the hand does not let go of the club, and even in contact juggling, as Gaëlle Bisellach-Roig has highlighted for example. Swinging manipulation has seen a first development with bright or flaming bolas, to the rhythm of a bola in each hand. Then it gave birth to the poï, very popular in the 1990s and in constant evolution. At first, it was a chain with a burning wick at its end. With the development of LED accessories, the poïs are being refined and in 2007, Ronan McLoughlin, with the help of Declan Mee, created a new version that could be used on stage without fire or light. It is a cord with a stage ball at one end and the handle of a club at the other.

The first person to distinguish himself through hat juggling was Paul Cinquevalli, who not only juggled with five hats, but also associated them infinitely in combinations with other objects. So, he places a hat, a coin and a cigar on an umbrella. With one impulse, he throws the umbrella into the air and recovers the hat on his head, the cigar in his mouth and the coin is placed on his eye just like a monocle.

Clowns often use conical, felt hats, which they stack on top of each other or throw at each other. In the 1930s, King Repp used straw hats like boomerangs. At the beginning of the 20th century, Paul La Croix invented a "hat bounce" act, which made Bela Kremo and his son Kris famous. The exercise is performed with a top hat thrown at the artist. Instead of catching it by wearing it, the juggler gives it an impulse with his forehead that makes it twirl in the air. When the hat comes back to the right height, the artist chooses to catch it or to throw it again in the same way, up to five or six times.

Distinctive forms

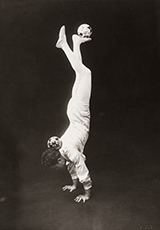

Antipodism is a form of manipulation with the feet. The artist lies on his back, on the ground, on a rug or sometimes on a special chair called a Tranka Hispaniola, "Trinka" or "Cochinette"1. This type of juggling borrows its technique from the Icarian games, Risley act2, which is played with human acrobats and not objects.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, the Kremo family distinguished itself both as antipodists and icarians. The first member of the Kremo lineage is the Viennese Josef Kremka. He trains his thirteen children in the dual discipline of which his son Karl continues the tradition. Bela, Karl's son, began his career as an acrobat in the family act before becoming a virtuoso solo juggler. His first show took place in 1933 in Aalborg, northern Denmark.

When a balance number is associated with the handling of a ball or plate and object throws, it is generally referred to as a combination. If all the objects in the combination are in balance, then we are talking about a "statue" number, which is reminiscent of the artist's perfectly immobile position in a precarious situation.

1. Editor's note: This chair, which places the artist in a position that facilitates manipulation, was invented in 1843 by an American, Mr. Devious.

2. Editor's note: Named after the American Richard Risley Carlisle (1814 - 1874), sometimes known as Professor Risley, who honoured this discipline.