From impetus to propulsion

by Marika Maymard

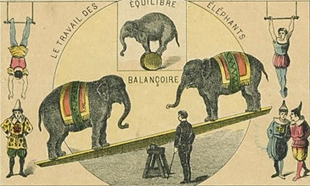

A simple plank set on an axle, set in motion by two people using their weight to shake and if possible unbalance their partner, the teeterboard in its simplest form dates back to the dawn of time.

Working with imbalance

In the 18th century, a society game offered at rich private follies, and a popular game played at squares, the Vauxhall gardens or tivoli, created at the time of the Revolution, the tape-cul or tappe-cul was present at every festive occasion. It appears numerous times on the programme of festivities held on April 2nd 1812, on the Champs-Élysées, to celebrate the marriage of Napoleon Ist and Marie-Louise of Austria. It appeared alongside games of rings played on real horses as a prelude to Franconi's equestrian exercises.

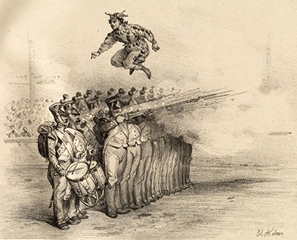

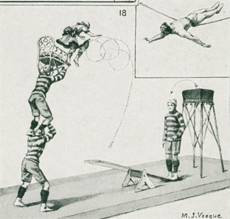

To raise themselves off the ground and give height to jumps, acrobats seek a source of impetus. The rigodon is a thrust given by a partner who, with bent knees, grabs the acrobat by a foot with both hands, and suddenly flexing his knees, helps launch the acrobat into the air. The petauron or petaurus (cited by the Greeks and then by Manilus in the Satires de Juvénal, book IV, as a small mobile plank or teeterboard), supplied mechanical thrust to help the athlete to glide like a petaurist, the scholarly name for the flying squirrel. In 1599, in his work, Trois dialogues dans l’Art de Sauter et Voltiger en l’air, Archangelo Tuccaro advocates and draws a small springboard that ensured the success of elaborate jumps. Finally, the great plank of the batoude long trampoline (from the Italian battuta), enable the jumper to use the impetus gained in the wings and to turn somersaults as he flew over a group of horses or soldiers with bayonets fixed, an act immortalized by Auriol in the mid-19th century.

But the 19th century floor acrobat, who used tremendous energy, and pure, muscular brute strength, was far from imagining the shake-up that would arrive in the shape of organised propulsion from the trampoline and teeterboard. The entire vocabulary of the floor acrobat, patiently developed, varied, and combined with jumps, balancing postures, elevations, and columns, suddenly found itself disqualified by the use of a trampoline, and re-employed, tenfold, in another dimension. Some seized this opportunity for renewal, but many refused this innovation from gymnastics. Athletes, unknown to the world of barkers, seized the new speciality acts, leaving frustrated acrobats in their wake.

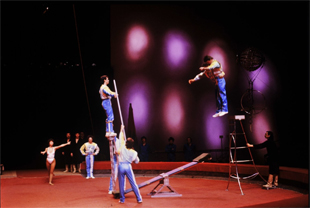

Renewing links with the cheerful tone and swaggering mischief of the early tape-cul, in which the tapeur or "hitter" was king, contemporary artists have taken up the Korean plank, a small, two-person teeterboard, alternating between being the pusher and the flyer. The latter is propelled higher and higher, performing curves and figures in the air, before coming back to land again on a few square centimetres at the edge of the plank. The imperious, mechanical and metronomic movement of the seesaw leads both partners into a game of jumps and rebounds, with spectacular results. Whether a duo, such as Alastair Davies and Jules Trupin in Saut en sol, or a trio, such as the small collective of Rémi Fardel, Jérôme Hugo and Amaia Valle, or even the five who make up the explosive Compagnie Bam: Guillaume Amaro, Thibault Lapeyre, William Thomas, Socrates Minier Matsakis and Sylvain Briani Colin, they can be unruly or serious, yet always remain masters of their performance.

Landmarks and references

by Christian Hamel

The teeterboard was child's play until the acrobats got hold of it and made it into one of the most spectacular and risky acts in the circus.

Historic landmarks

It was a man named Wotpert (sometimes spelled Wolpert) who presented, in a duo with Paulan, the first form of the act in 1903, at Tichy's in Prague, then at the Wintergarten in Berlin. The great floor acrobatics families at first thought it was some kind of illusion, but soon understood that they could make use of it to perform an increased number of somersaults and to build higher human columns.

In 1904, the Austrian Glinserettis turned a double somersault using a teeterboard. The same year, the Picchiani family succeeded, for the first time ever, in propelling an acrobat up onto the shoulders of the fourth man in a column. In 1917, Venus of Germany, the Metzettis and their star acrobat Sylvestre Metz managed a quadruple somersault, followed by a landing in an armchair held by a partner. This performance was copied by the Argentinian company the Yacopis, who in 1941, successfully managed to land an acrobat on the fifth level of a human pyramid for the first time ever. Sylvester Metzetti went on to have a Hollywood career under the name of Richard Talmadge.

Alongside these Latin companies, a Budapest school developed with George Losonczi, who had created the first internationally renowned Hungarian company – the Faludis – before 1914. Among his pupils, Ferenc Gondör created the Magyar company and Karoly Hortobaggy founded the Great Hortobaggy company. In 1929, the Breiers successfully performed a triple arrival on the second level. The Hungarians adopted folk costumes and chose to perform to Brahms' Hungarian dance n°5 . They experimented with tandem jumps, jumps with pirouettes and in particular, the double on the fourth level, simultaneously achieved by three of their companies at the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey circus around 1970. They also developed a formula on a small teeterboard with only two or three artists, based on the model of the Sturla sisters in France. We can also cite the Binder-Binders, the Kristoffs and in particular the Mazottis, whose acrobat Mariann Teszak successfully performed the triple daredevil.

Developments

Progress in the 1970s was to come from Bulgaria, first with the Silagis and their landing on the fifth level of a human column, then the Kehailovi, who in 1977, managed to land on the seventh level, a feat imitated the following year by the Kovatchevis. The Balkanskis worked wonders with the column, performing triple somersaults and double-doubles landing on the fourth level. Nikolay Balkanski succeeded in performing a double somersault with one stilt, but the best examples of this type of performance came from Russia, with the Dovjenkos (double-double and triple on one stilt), and the Pouzanovs (triple with triple pirouette).

The Berosinis and the Biros combined teeterboard jumps with Icarian games. Albert Micheletty regularly succeeded in landing on the fourth level of a column set up on a unicycle, while the Picards jumped from a teeterboard onto their horses, and Adèle Nelson jumped from the teeterboard onto an elephant's back. Today, René Casselly Junior performs the quadruple, with a landing on an elephant's back.

Neoldduigi is the name given by the Koreans to the traditional teeterboard created by women during the Joseon, or Yi dynasty (1392-1910), and which is still practised in city parks. Two partners face-to-face, jump and are propelled in turn on either end of the plank. Pyong-Yang companies perfected this work, and in the 1930s, the Picchianis adopted this system to add rhythm to their performances. Trained at the National centre for circus arts (Cnac), Rémi Fardel succeeded in performing the triple and the double-double in this configuration.

Maintaining the level of performance while imagining performance scenarios is a challenge that many artistic directors want to take up: in 2002, at the Festival mondial du cirque de demain, Andreyi Kovgar presented an act inspired by the world of Chagall. Following on from the "Nouveaux Russes" who jumped in tailcoats, Alexandre Grimailo gave us a veritable masterpiece with an act entitled Amadeus, performed by the company of Dmitry Sokolov, a former member of the Kovgar collective, with whom he toured for ten years before starting his own company.