by Pascal Jacob

Since he has been sedentary, man has always wanted to surround himself with live animals: for breeding and companionship purposes, but also as a means of asserting his almost absolute power over nature and all things, whether they are close to him or from distant lands. To a certain extent, the cabinets of curiosities of the 16th century are both an echo and a prelude to the menageries, which were an eclectic and diverse group of creatures and inanimate objects designed to amaze, but especially to create a desire to own more.

Royal collections

Before opening up to an ever-widening public, the first menageries were royal or princely. They reflect the sovereign's taste with pomp and originality while suggesting his ability to identify, acquire and organise collections that are sometimes extraordinary. As a pretext for numerous scientific observations, they also offer a formidable repertoire of forms to painters and sculptors who gravitate in the monarch's entourage. Fauna and flora, presented in a new and symbolic architecture, thus give birth to other collections, but they also contribute to the emergence of a different view of the world.

Versailles, Schönbrunn, Chantilly, to name but three of these prestigious residences, are home to menageries where birds and mammals live together, subjects of fascination for the court and its guests. This appetite for exoticism spreads to all segments of the population and the first travelling menageries were created at the end of the 18th century. These usually consist of a few animals exhibited in an inn yard or under a tent, but the success is constant. Reptiles, monkeys, brightly coloured macaws or small cats make up the first base of these menageries before the arrival of the big wildcats and a long procession of unexpected creatures, from armadillos to iguanas and from rheas to rhinos, were made available for the greed of the menageries' owners. A new threshold is crossed, and the cages are filled with unknown animals.

Modern beasts trainers

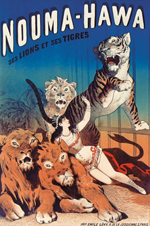

Inevitably, very quickly, the mere presence of wild beasts was no longer enough to attract the early crowds and at the beginning of the 19th century men like Isaac Van Amburgh, Henri Martin or James Carter, heirs of the Roman wild animal tamers, definitely abolished the limit imposed by the gates. They enter the cages and subdue their animals with a clever mix of constraints and rewards: modern training was born. The major problem that hinders its development is linked to space: wild animals are tamed in the cage where they live, i.e. a small area of a few square metres whose narrowness accentuates the danger.

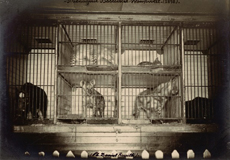

The first transformation will consist in the implementation of a performance system based on the repetition of sessions or, in rawer terms, on what is called culling: up to ten performances per day in front of an ever-changing audience. A "theatrical cage" is installed in the centre of the menagerie, larger than the rolling cages of the wild animals which are aligned on each side of the central stage. A row of carriages is empty. All animals are kept in the other row of cages and their arrangement determines the order of the program. For the following representation, this order is reversed. The audience sits or stands in front of this frontal device and appreciates the brevity of the show, which is similar, all things considered, to the duration of a bullfight. The tamers are the stars of the fairgrounds and their fame often crosses borders. The repertoire evolves little and it is the "manner" that allows these men and women to distinguish themselves in their daily confrontation with the wild animals.

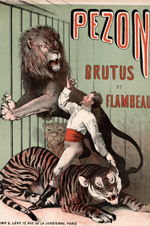

Fairground Princes

When François Bidel entered the theatrical cage of his menagerie, he was dressed like a bourgeois, but with his martial appearance and his long hair thrown backwards he was faithful to the nickname given to him by Victor Hugo, Leo inter leones. He captivates the public and worries his wild animals. A high society tamer, he gathered together the workers and aristocrats in front of his cages, all of whom were fervent admirers of a man who was as comfortable with his lions as he was with a monarch. Bidel has a singular style, different from Edmond Pezon's, who is more like a land tamer, peasant at heart, dressed in corduroy trousers and a simple white shirt tightened in a wide fabric belt. We are far from the sky-blue dolman underlain with silver of the Amar brothers, "the youngest tamers of their era", proudly lined up on the stage of their menagerie a few years before they created their first circus.

The links between the fairground world and the circus were forged at the end of the 19th century when trainers were hired on an occasional basis for a series of performances in Paris, Vienna or Berlin. But long-time fairground entrepreneurs, such as the Chipperfields, who have been present on British fairgrounds with animals since the 16th century, will abandon traditional exhibitions and focus on running large scale circuses.

The revolution came from Germany, driven by Wilhelm Hagenbeck, Carl's brother, creator of the zoological gardens without bars where animals, prey and predators, give the illusion of living in perfect harmony. The Hagenbecks have been animal dealers since 1848, but they quickly decided to expand their activities by offering their clientele groups of trained wild animals. In 1889, Wilhelm Hagenbeck, sensing the rise of a rapidly changing circus, invented the central cage, which could be dismantled in several sections to match the diameter of the ring and allow a larger number of wild beasts to be presented at the same time.

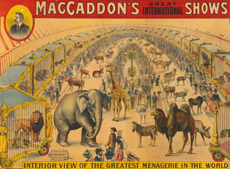

Circuses will rush into this unexpected breach and integrate more and more animal numbers into the structure of their programs. It is the advent of the concept of the circus-menagerie, born between the two world wars, but it is also the end of these travelling exhibitions which have contributed to developing a taste for exoticism throughout Europe and America.

The wild beasts play the leading role, some establishments go as far as presenting three trained groups in the same programme, but very quickly elephants, camels, sea lions or giraffes enter the arena and help to remove the horses from the scene. A new story begins.