by Pascal Jacob

An iron and wool lion, locked in a cardboard cage, its mouth wide open so that its tamer can stick his head in it, simply manipulated by his creator as children do with their toys. Under the eyes of a handful of amazed spectators, Le Cirque by sculptor Alexander Calder is a synthesis of the imagination, a construction of the mind, a work of art shaped with the care of a craftsman: all the archetypes of the circus are embodied in a multitude of small silhouettes with prominent symbols and dressage is well represented with a menagerie that is magnificently crafted, both refined and bursting with humour.

Beasts and forms : representations

Savage or wild, much like barbarian, is an antonym of civilised: quite an interesting paradox if we consider dressage to be an attempt at civilisation applied to ferocious creatures or animals that are just not at all receptive to taming. From the original selva, the savage or wild marks the border between humanity and animality. Under French law, the fact that the animal described as "wild" is by definition not kept is another interesting contradiction in a context of forced captivity. In Chinese symbolism, only wild animals matter: pets do not count, they have no role to play and they are confined to a foolish posture in superstitions and tales…

In dressage, the taming process is often a prelude. When Prince Tamino, the hero of Mozart's The Magic Flute, charms the wild animals gathered around him, he reinvents the myth of Orpheus by ensuring an intuitive connection with the idea of representing an idyllic exchange between men and beasts [Wie Stark is nicht Zauberton, see section 6]. This duality was a source of fascination: Leonard Tsuguharu Foujita's painting La Dompteuse in 1930, like the lithograph representing a lion in front of its tamer that the Norwegian painter Edvard Munch (1863-1944) produced in 1916 – The Lion Tamer –, suggested the appetite of plastic artists for a subject that could, at best, be anecdotal. Nevertheless, this taste for the wild, for tousled manes and sharp fangs has crossed and transcended all periods since the 18th century.

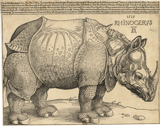

In 1751, Clara, a perfectly tamed rhino who had arrived in Rotterdam ten years earlier, was presented in Venice for the Carnival. Its success was extraordinary, and the painter Pietro Longhi came to capture this mythical animal on several canvases. The beast is rare and as such, it is particularly fascinating to the public and chroniclers of the time. Clara is not the first animal of its species to step on the ground of the Old Continent. Two centuries earlier, the painter and engraver A. Dürer had created an engraving of a rhinoceros offered to the King of Portugal in 1513. The beast is rare and as such, it always fascinates the public and chroniclers of the time. Little by little, the exotic animal becomes a subject and, sometimes, an allegory of fierce independence when it induces a certain nostalgia for travel and discovery.

Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo drew a series of sketches around 1800 in which animals are depicted with his polichinella: one of the drawings shows a cat in a cage, similar to those of the travelling menageries that were touring Europe at the time. This taste for the world around us resonates perfectly with these brightly painted caravans that occasionally settle in a village square and reveal their secrets several times a day with, in addition, the extra spice of a cage entrance. It is clear that after contemplating a lion or a tiger, either slumbering or roaring, people expect more the next time they have the opportunity to venture under the canvas of another menagerie... Paul Meyerheim is a German painter who prefers genre scenes. He is infatuated with the scent of the wild animals, as heavy and pungent as the thick smoke produced by the quinquets argand lamps attached to poles stuck in front of the cages. The menageries where the strangest animals are crammed together exert an irresistible attraction on his imagination. He paints many canvases, sometimes in a very large format, and thus reflects a singular atmosphere, specific to these rudimentary huts where all segments of society are present. Meyerheim's paintings are hung in the salons and picture rails of museums, thus offering a popular and fairground form an unexpected social positioning and lasting recognition.

Influences

From the beginning of the 20th century, more than the clown, the horsewoman or the trapeze artist, the wild animal has permeated the aesthetic fabric of the circus: plastic artists and authors were not mistaken, the beast, furs, scales and shells combined, is an extraordinary catalyst of creativity and inspires many artists with powerful canvases and striking sculptures. An inexhaustible repertoire of shapes is open to all those who choose to represent animals with flexible lines. The bestiary sculpted by Giambologna to decorate a fountain in Florence in the 17th century reveals his ability to capture the thrill of life. Rosa Bonheur, Arnost Hofbauer, Emmanuel Fremiet, Antoine-Louis Barye Bugatti, François Pompon, Georges-Lucien Guyot, Edouard Marcel Sandoz or Guido Righetti, use the living to create a repertoire of forms that inspire them and from which they define their own style. With them, animal sculpture asserts itself as a genre in its own right and for some of them it becomes the main theme in their work. Represent to appropriate: the countless models that adorn consoles and fireplaces reflect the taste for the rest of the world, but also for a false proximity with extraordinary creatures.

The influence of the savage and the wild is also perceptible in literature: Une passion dans le Désert, a short story by Honoré de Balzac published in 1830, begins with an evocation of the tamer Henri Martin, whose work with the wild animals is a pretext for a touching story of complicity between a soldier lost in the desert and a panther. In this fortuitous proximity between man and beast, we find the origins of the story of Androcles, a slave who fled to treat a wounded lion in the desert before being recaptured, condemned to be thrown to the beasts and spared by the lion he had rescued. The parable, set under the reign of Caligula, is recurrent in Roman history: Pliny the Elder reports two similar anecdotes where Mentor of Syracuse and Elpis of Samos also rescued wild animals, but he does not specify whether they made such precious friends as the lion of the young slave! But the adventure is very pleasant: the British playwright Georges Bernard Shaw published his version of the story of Androcles in 1912, which provided the script for a film by Chester Erskine made in 1952.

The American writer Nathaniel Hawthorne mentions in his diary the presence of a menagerie near North Adams, Massachusetts, which he visited in September 1828 and where he saw a charismatic tamer, undoubtedly Isaac Van Amburgh, slip his arm and head into a lion's open mouth. He insists above all on the effect produced by this man's magnetism on the audience, much more than on the feat itself…

It is hard not to see in this human practice of rubbing shoulders with the wild animal strong links of anteriority or posterity, imagery, mythical or legendary. Androcles, Orpheus, Circe, but also Daniel or St. Francis of Assisi, firmly embed the discipline in a very humane perception of an animal kingdom destined to be subjected above all to the good will of men. In composing his initiatory work, the British writer Rudyard Kipling portrays a child raised by wolves and able to understand the language of all the animals around him. Mowgli, the fragile hero of the Jungle Book, is no more of a tamer than Lord Greystoke, the Lord of the Forest from another continent, but they embody that edenic complicity that man sometimes dreams of feeling or living.

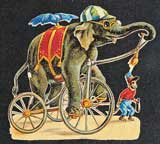

This attenuation of the sharp line between what is wild and what is civilised is assumed and transcended by humorous environments where the creators find their inspiration deep within the friendly vein of dressage, ignoring man and concentrating on the beast. With Walt Disney and Tex Avery, an enchanted bestiary populated the big screen with lightning speed at the beginning of the twentieth century. This "menagerie" owes much to the imagination and romanticism of the tamer, benevolent master of his humanised animals, sometimes to the point of excess. Thus, the crowned lion, perched on a chariot pulled by two tigers, the elephant wearing a cap and on a tricycle or the chimpanzee dressed with elegance from head to toe and smoking cigars, beyond pathetic attempts to assimilate them to thoughtful creatures, represent instead a contrario an extraordinary creative force which culminates in an unsettling status as denatured and unnatural animals.

From interpretation to fragmentation, there is sometimes only a very slight leap to the side. Clawed legs to decorate table or chair legs, stylised scales, furs and skins stretched over a multitude of armchairs and day beds, stripes and ocelli reinterpreted as stylistic figures, the decorative arts have drawn from the endless pool of wildlife since Antiquity. If the accuracy of the representation is given pride of place in the first instance, creators will gradually free themselves from a repertoire of forms considered too precise to allow for an unbridled imagination to take shape. As such, the elephant is one of the most sought-after creatures by furniture designers: the Elephant plywood stool created by Charles Eames in 1945, the Elephant Stool tripod designed by Sori Yanagi in 1954 or the Elephant chair designed by Bernard Rancillac in 1966 attest to this fascination for an extraordinary creature. The design of the polar bear sofa created by Jean Royère in 1953 fits in well with this blueprint style that is so characteristic of the productions of these fertile years. The extras are back with the "useful" creatures imagined by Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne whose enchanted and humorous bestiary consists of both pragmatic and poetic animal-furniture. The work of Maximo Riera, Derek Pearce or Benoît Convers constantly flirts with irony and mismatch but never forgets to think about the integration of these wooden or metal beasts into a daily life that sometimes lacks fantasy.

We know Walt Disney's strong taste for an anthropomorphic perception of the animal. The sources of his work are often explicit, drawing heavily on the roots of European culture. The fables of Aesop, the tales of Perrault, Andersen or Grimm, the expressionist cinema and... the animal world in all its splendour, constitute such a powerful basis for his inspiration.

"Strong as a bear", "cunning as a fox", "sober as a camel", "turning like a lion in a cage", "shedding crocodile tears" or having an "eagle eye" are all popular sayings that have been created with a very humanised feeling of the animal world in mind. They reinforce the underlying fascination with the wild, which has crossed cultures and civilisations since the dawn of Humanity. A way of appropriating the virtues and values of the animal kingdom to further affirm this obscure desire of any power that haunts men when they are confronted with a nature that they too often consider hostile. Wild.