by Marika Maymard

The idea of turning wild animals into submissive creatures and exploiting them for glory has always been part of the relationship between man and nature since the dawn of time. A relationship where fear meets admiration, a confrontation that turns from a protective reflex to passion and enchantment. The warrior adorns himself with the attributes of the killed animal to symbolically claim its courage, in turn inducing fear and summoning glory for conquering indiscriminate force. This conquest represents a first form of appropriation. The exhilaration it provides turns to obsession. Yet another conquest, killing, bringing back trophies or capturing and exhibiting is both an existential goal and an alternative to the overwhelming burden of heroes trampled on by lost military campaigns. The 19th century revives against the "savage", beasts and men, the questions and desires of a society driven by the achievements of Progress and the retreat of borders.

Facing the wild

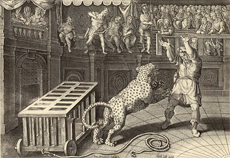

Fighting wild animals on the doorstep, like bears, wolves or lions depending on the region, is a vital issue. The need for confrontation becomes a game, a spectacle, when, out of idleness, a desire for power or revenge on adversity, a man, king or emperor organises a gigantic raid on wild animals and a slaughter and bloodbath ensues. The first link between the circus and the exploitation of wild beasts originated from the ludi offered to the Roman peoples inside the amphitheatres built throughout the empire. Consisting of hunts – venationes – and fights between men and animals, circus games consume by the hundreds the wild animals brought back from the submissive regions. According to Dion Cassius, the only inauguration of the Colosseum, the Flavian amphitheatre, by Emperor Titus in 80 CE, justified the killing of 9,000 tamed or wild animals during the 100 days of festivities. The games disappeared with the fall of Rome in the 5th century, but they are reflected throughout history, in fights and animal shows. In arenas set up around city gates, dogs are thrown at donkeys, wolves at bears, hyenas at bulls. Thus, prior to the invention of the modern circus in 1768, the "Circus" of the rue de Sèvres spread its stench and the screams of its bloodthirsty fighters in this suburb of Paris. Destroyed in 1778 to build the Hospital for Sick Children, it was rebuilt at the Barrier of Pantin.

The organised exhibition

Since the exhibitions of bear shows in village squares at the dawn of time, the whole chaotic history of human domination over wild creatures has been unfolding. An existential and economic challenge, the exhibition of exotic animals is accompanied by a range of justifications, from entertainment to scientific study. The fairs are full of "Professors" who present in a Latinising and emphatic vocabulary "wonders of nature" taken from their environment, labelled according to their degree of strangeness, encaged, chained, and inventoried on the posters on the walls, "By permission" of the prefect of the town.

The representation framework is gradually being organised. From the bloody and nauseating chaos of the Roman arenas to the stylish presentation in colourful uniforms of the circus cage entrances, all the stages of a dramaturgy are developed. The wildlife theatre begins in the shade of the "theatrical cages" lined up behind the bevelled mirror facades of the fairgrounds.

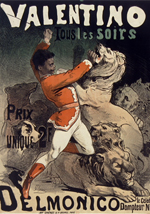

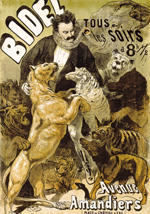

It consists at least of a set, actors prepared for the performance, and a master of ceremonies. Among the cast, the most expected are wild beasts, big cats, tigers and lions, and small cats, panthers and leopards, jaguars, pumas and lynx. But bears, hyenas and wolves are also wild animals. The first tamers, Henri Martin, Isaac Van Amburgh and James Carter, performed on stage in pantomimes around 1830. A chronicle of Parisian life described in 1829: "Mr. Martin's menagerie located at rue Basse-St Denis. It features two lions, a Bengal tiger, the Asian hyena and the Peruvian lama. Each one is tamed and plays with their master".1 It takes almost a hundred years before the wild beasts, educated, trained or tamed, move from the theatrical cages to the central cage of a circus ring. The first circus-menageries were called Amar, Bouglione, the Zoo Circus des Court, in France, Kraiser or Krone in Germany, Chipperfield in England, Kludsky in Czechoslovakia, Van Amburgh in the United States…

Fatal face-to-face encounter

From the moment the tamer and the animal are present, they are committed to each other, dependent on each other, in the city as well as on stage. The tamer, a low-ranking officer of the imperial house in Rome, in charge of the wild animals intended for "animal entertainment", must teach them to parade in the arena before fighting according to an orderly process. Beware if the animal spoils the show by skipping the steps, to jump on the dedicated opponent and shred it too quickly or conversely, if it falls asleep on the hot sand! The tamer prepares "with his bare hands", in a relationship that he wants to base on mutual trust combined with just the right amount of threat. This method was called "petting" in the 19th century and was said to have been adopted by Martin in the theatre, as opposed to "ferocious" dressage, which was more readily used by the fair's beast trainers for its terrorising power. The inevitable face-to-face contact between the trainer and his animals from the very first contact will determine their understanding of one another, their behaviour and their character. The future of their alliance will never be safe, despite all the attention paid, the expertise provided and the constant vigilance. Alfred Court (1883-1977), a daring tamer, who was passionate and listened to, achieved success throughout the West with groups of wild animals led by tamers chosen for their skills and strong character. He professes, and gives accounts, in articles and books. But eventually, he mourned the loss of several of his tamers.

Dressage: a gender issue?

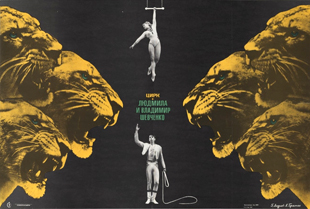

If the powerful lever that can push someone to embrace the career of a tamer is the desire to feel that they exist freely with force and passion, then women and men alike can aspire to it. The resources to be found within oneself, the love of animals, a perfect composure and a great obstinacy, are not the prerogative of one gender only. What brings the female tamers closer together and differentiates them from their male counterparts is the way they exercise their domination over their beasts. Madame Morelli wears an evening dress and pearl necklace for her jaguars, Claire Héliot gives her lions school lessons and serves them soup at the table, and Tilly Bébé cuddles the animals she has inherited from the Countess of X*** who had given them up, just as if they were her own children. Independent and imperial like Nouma Hawa in the previous century, Irina Bougrimova lays out her lions like a carpet on which she walks down from a flying basket where she was sitting with her favorite lion. Margarita Nazarova plays polo with her tigers in a pool barely equipped with bars or makes them work from small sofas hanging from the cage.

Women tamers have long been in the news. Some of them work quietly, others have to push a little harder to assert themselves in front of men, for fun, provocation or seeking revenge.

Feminists like the German Lily Braun refer to them as pioneers in a struggle for personal identity, while Irina Bougrimova, a former gymnast who has become a tamer, influences a whole generation of Soviet trainers.

With the gradual abandonment of cage entrances by the major circus companies, the door, ajar less than a century earlier, on a universe littered with strong smells and crammed with thrilling furs, roaring rage and blowing disaster, is gradually closing down. Forever.

1. in La vie parisienne à travers le XIXe siècle : Paris de 1800 à 1900, T. 1 / supervised by Charles Simond (1837-1916), Paris, E. Plon, Nourrit et Cie, 1900-1901.